Creating a financial plan to help you meet your legacy goals isn’t about implementing one or two specific strategies, but instead is about looking at all your financial decisions through the lens of those legacy goals, and that includes the construction of your investment portfolio.

While constructing an appropriate investment portfolio is relevant to every investor, its value is often most apparent in the pre-retirement years (usually between the ages of 50 and 65). By this stage of life, most people have gotten debt under control and have begun to accumulate a portfolio of assets, and the larger a portfolio grows the larger the ramifications of portfolio management become.

How a portfolio is constructed and the investment philosophy that is followed has huge implications for the amount of wealth surplus (i.e. money over and above that needed for retirement spending) leftover for legacy giving.

Why investment philosophy is important

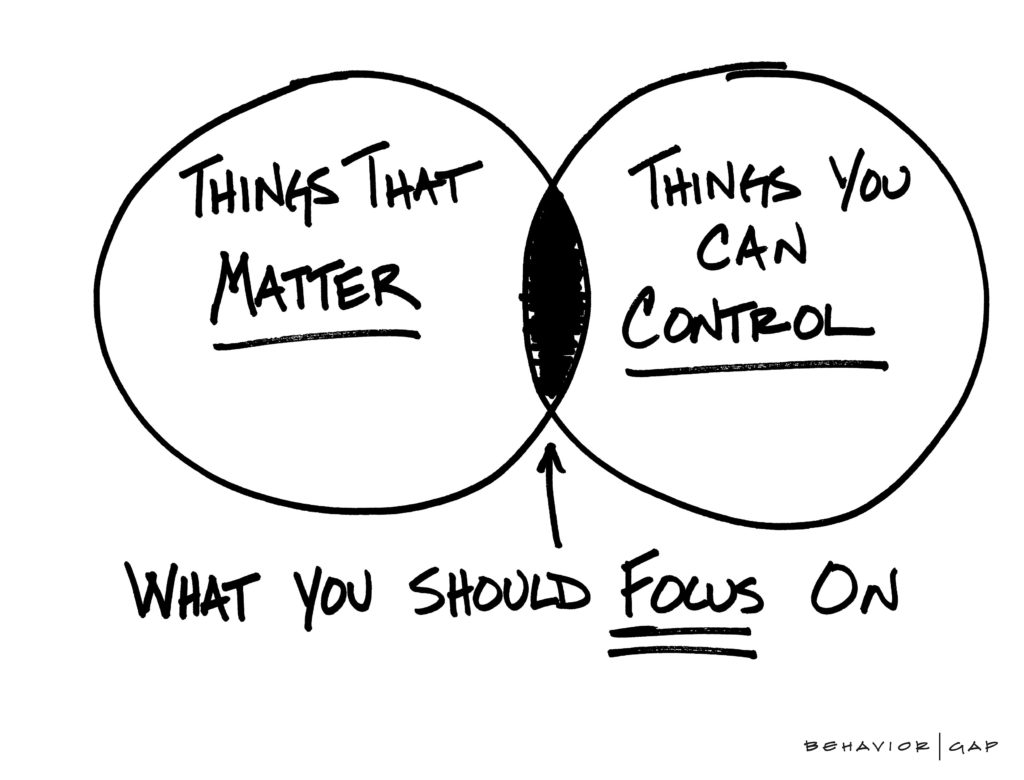

Carl Richards has a great sketch shown below that I think perfectly illustrates sound investment philosophy. It is a Venn diagram, with two overlapping circles. One of the circles is titled “Things that matter”, while the other circle is titled “Things you can control”. It is the middle overlap area – the things we can control that actually affect portfolio performance – that we want to focus on when it comes to investing.

There are plenty of things that affect your investment performance that you have no control over, like what the Fed is doing with interest rates, the inflation rate, or how fast the economy is growing. Since you can’t control them there’s no use worrying about them. These factors define the field of play for all investors and set boundaries on the investment performance you can expect to see in your portfolio.

For example, there is no escaping the gravitational pull of a low interest rate environment, so it is better to accept this reality and adapt rather than trying to fight it by “reaching for yield”, which requires compromising diversification.

So, what is in the middle overlap area of that Venn diagram? Well, for starters, diversification and cost. These are two things we have direct control over that have huge implications for long-term investment performance, which means we really want to get them right. Whenever I construct portfolios for clients, one of my overarching goals is optimize the risk/return relationship of the portfolio. In other words, I want to get the most return for a given level of risk.

Regardless of where we decide to land on the risk spectrum from conservative to aggressive, I want to make sure we’re squeezing every last drop of return out of each increment of risk we’re taking on. And the way we do that is primarily through maximizing diversification and minimizing costs (including minimizing taxes). This is most easily accomplished with broadly diversified, low-cost index funds, though there are exceptions.

Why should you rebalance your portfolio?

Another factor in the middle of that Venn diagram is rebalancing regularly. I think of investing kind of like gardening. If you plant a garden and then walk away and forget about it, eventually that garden will become overrun with pests and weeds, making it less productive and fruitful than if you had actively tended to it. Similarly, with investing, if you want your portfolio to be as productive and fruitful as possible, there is basic portfolio hygiene required, and rebalancing is a big part of that.

Over time, as markets fluctuate, your stocks will grow faster than your bonds or cash, so your portfolio will tend to drift more aggressive and become stock heavy. Rebalancing involves periodically selling the relatively outperforming asset and buying the relatively underperforming asset to stay on track with the target allocation. Not only does this ensure you stay within the appropriate risk range, but every time you rebalance you are effectively selling high and buying low – not a bad formula for investment success.

How do emotions impact investing?

Finally, another factor I would place in the middle area of that Venn diagram is maintaining discipline over the long term. The markets have always gone up over the long term and are exceedingly likely to continue rising in the future. It is a fundamental truth of market dynamics: in order to induce you to take on the risk of investing in the markets, the markets must compensate you in the form of some sort of positive return over time. If that were not the case – if you were expected to lose money in the markets over the long term – nobody would invest, and the markets would cease to function.

The key to long-term investment success is staying invested throughout the ups and downs to capture the long-term market return.

Having said that, we are all human beings subject to human emotions, so maintaining discipline in the face of market downturns is never easy. Determining the appropriate portfolio allocation is more of an art than a science because we’re trying to thread a needle. On the one hand, we want to have enough equity in your portfolio to achieve the growth needed to meet your future spending and legacy goals (stocks are the growth engine of a portfolio, after all). But, on the other hand, we also want to make sure your portfolio is not so aggressive that there is more volatility than you can handle in a down market. Too much volatility in your portfolio during a down market may tempt you to sell out of the market, which only short-circuits the process of capturing the long-term market return and typically does more harm than good.

Emotions and investing don’t mix. Studies have shown that the average investor underperforms the stock market by 2-4% annually (that’s a big bite out of your future legacy giving, especially compounded over many years!), and it’s typically because emotions have clouded the investor’s judgment. The investor who panics in a down market and pulls out of the market usually ends up locking in losses, and by the time they feel more comfortable getting back into the market, most of the recovery has already happened. So, they end up shooting themselves in the foot on the way down and on the way back up.

Fortunately, a good financial advisor can serve as an emotional circuit breaker. Since they don’t have the same emotional connection to your portfolio that you do, they can help you to maintain a long-term perspective.